All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

The Attic

2005

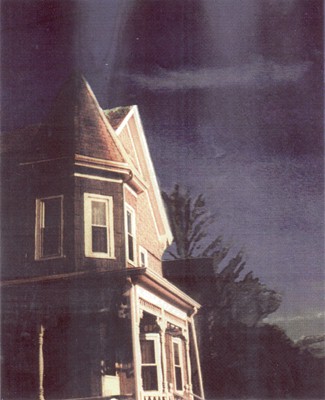

It was one of those evenings that reeked of oppression. The street was desolate, and not a peep could be heard. It was as if the slightest sway in the wind or perhaps the awry drift of a single follicle of dust, would disturb the perfect silence. The red brick houses that lined the street, glowed dimly with warm, incandescent light that contrasted with the stark frigid air outside, threatening to break through the fragile glass of the windows. The girl’s house stood at the end of the street, glowering in it’s former glory. A Victorian mansion, unyielding despite it’s decay. It was cold inside. Cold and dry.

The girl gazed at the house across the street as she often did on evenings like this one. She could see inside the front room from her perch on the windowsill. Two young boys drank hot cocoa. Their chocolate stained mouths laughed silently as a lean woman with a warm smile tickled their tummies. The girl could see the outline of their little bodies shaking, their heads thrown back in delight.

The silence was suddenly broken by the loud twist of the faucet handle, creaking from down the hall. A roaring rush of water followed immediately. She knew what was next-- it was bath time. Her father lifted her into the tub as he always did on evenings like this one. The pressurized water was sharp, pounding down on her soft skin with force. The girl closed her little eyelids, so thin they could tear, and hummed her favorite song. Somewhere Over the Rainbow. Her mother used to sing the song to her before bed every night, rocking her slowly in the old wooden rocking chair in the corner of her room. Her voice was rich and velvety like Judy Garland’s, and it had soothed her. But the girl was six now, and as her mother had told her, six was too old to be rocked before bed. She was a big girl now.

The girl continued to hum to herself as she felt her father’s leathery skin rub against her soft back. His fingers grazed from her jutting collarbone, to her spindly legs. That’s all she ever remembered. His rough skin, her pruney fingers, and the neverending rush of cold water.

2014

Mae

My bedroom walls are yellow. And not the pretty kind. The dull kind. The depressing hue of mustard, and possibly the ugliest color imaginable. Yet here I find myself sitting on my bed and staring at such remarkably unpleasant walls, just waiting to see if they get any uglier. They’re bare, and flakey pieces of paint are starting to chip off. A thick layer of dust coats the rotting hardwood floors. The decoration in my room is sparse. There’s the cast iron bed frame that supports my skimpy mattress, and the chest of drawers-- filled with ragged pink dresses from middle school. On the chest sits my china doll collection, Mother bought dozens of them for me. I only ever used them for staring contests.

Mother used to take such care of our house. It was undoubtedly, the loveliest in the neighborhood. Pristine white wood with red trimming. Mother inherited the house when Grandfather passed away, and she spent all her time polishing the hardwood floors, straightening the mint cream curtains, and dusting the satin tuffets in the living room. Her favorite though, was working in the garden. She worked for hours, planting bluebells. That was back when my father lived with us. I think maybe she did it all for him. All the cleaning, all the gardening. Strangely enough, I hardly remember him at all, just that he was gone by the time I was nine. My father, the gray business suit that poured my orange juice in the morning before it left for work-- and nothing more.

Shortly after my parents separated, my father was offered a job in London and didn’t hesitate to take it. He never looked back. When I ask Mother why they separated, she always replies with a laconic, “he was a bad man.” He broke Mother. Now it’s just us in this monster house. Our monster that’s still beautiful.

“Mae,” Mother’s tired voice echoes from three stories below. “‘We’re running late.”

“I’m coming. GOD!” I yell a little too forcefully. Sometimes I forget how fragile Mother is. She’s worn herself so ragged, dealing with all my “episodes.” That’s what Dr. Howell calls them anyway. I drag myself down the stairs, my head hanging low. There’s no way to glamorize therapy.

Mother drives me downtown to meet with Dr. Howell every Tuesday and Thursday afternoons in our BMW that smells like tobacco and peppermint air freshener. We sit in solemn silence for thirty long minutes. I stare at Mother the whole time. Her hair has gone grey and sits in a tangled heap on top of her head. She appears to be focused on the road, what’s directly in front of her, but I know her silver eyes are far away in another world. Her silver eyes creased with worry wrinkles. She’s aged so much over the past several years. Or maybe she’s just given up on trying to be beautiful.

I remember when Mother used to powder her face and paint her lips cherry red, like the china dolls she bought for me. She wore expensive silk Prada shirts and curled her platinum blonde locks into ringlets. I remember when I was a little girl, I would look up at her and think Mother is perfect. Even when she worked in the garden, even when she sat alone in the house, she always looked beautiful. Now her skin is raw and her striking eyes are weary. I don’t know when everything changed. We’ve drifted apart and it makes me sad. I don’t know how to fix it.

Finally, we pull up outside the sad little building where Dr. Howell’s office is located. A low guttural groan erupts from the pit of my stomach, and it takes all of my effort to roll slowly out of my seat and push the impossibly heavy car door open.

“Honey, please. Try,” Mother says. I never know quite what she means by “try” but I respond with an indifferent nod. She looks like she wants to say more, but sighs softly and looks the other way.

“I’ll be here waiting,” she says. I slam the door a little too loudly and walk away.

Dr. Howell is a slender women with a long nose, sleek chestnut hair cut into sharp bangs across her forehead, and a no-nonsense attitude. It’s not that I don’t like Dr. Howell. In fact, I find her businesslike approach far more amenable to my situation than my previous therapist, Lara, who thought we were best buds and called me “girlfriend.” It’s therapy in general that unsettles me. I feel as if I’m being pried open. As if Mother is just waiting for me to have some sort of grand epiphany. And when it never comes, it’ll just be another disappointment.

“How’ve you been Mae?” Dr. Howell’s serious voice inquires.

“fine,” I reply flatly.

“And why is that?”

“I feel… calmer than usual.” This is not true by any means.

“Are you telling me the truth Mae? Because, your mother called me on Sunday night. She’s worried about you, you know. She says you were really panicking. Mae, none of us can get inside your head but you. You’re the only one who know’s what you’re feeling. This is why your mother and I really need your cooperation. I feel like we’re finally getting somewhere. I believe in you.” Dr. Howell thinks I’m on the verge of a “break-through.” But I’m still struggling to figure out what that means. This is why I hate therapy. It’s manipulative. I’m not trying to make Dr. Howell’s job difficult. I want so desperately to tell her what she’s waiting to hear so she can just fix me already.

“What do you want from me?” I ask. It seems like a callous way to put things, but the words escape in soft whisper.

“I want you to figure that out on your own, Mae. Why don’t you think about that for homework and you can tell me your thoughts on Thursday. Okay?”

“Fine.”

“Why don’t we discuss what triggers your episodes.” Episodes is our nondescript way to reference my panic attacks. Mother started taking me to therapy last year when first noticed them. She would hear me scream in my room, and see me shake uncontrollably.

“It starts with something small like a smell or a sound. I can’t pinpoint exactly what or why,” I say.

“Can you specify? What happened Sunday night?”

“It was the attic.”

“What about the attic? Why were you up there?”

“My mother asked me to bring down the extra soap. We store it up in the spare bathroom. When I got up there, the anxiety started. My heartbeat was fast, and my legs were shaking, like the other attacks. My mother came upstairs when she heard me screaming. But then the panic stopped, and I just felt numb.”

“Good. That helps. Can you expand?” I really try to remember now and it takes a lot of effort to dig that deep inside the back of my brain, where I store everything I don’t want to remember.

“I didn’t feel like myself. It was like I was watching myself in a movie. It always feels like that.”

“What do you mean?”

“Like...like I’m out of my own body, and my thoughts aren’t even my own. And after that I just don’t remember. Then, all of the sudden I’m here again and I have no recollection of where I was before...This is why I can’t help you.” I’m surprised by the words that escape from my own mouth.

“Good, Mae. Acknowledging the things about ourselves that might scare us to a certain extent, is an important part of the process. I think you’ve really been starting to make some progress these past few sessions. Do you remember the project I assigned to you on our first session a few months back?”

“The scrapbook?”

“Yes. I think it would be very beneficial for you to work on it tonight. Okay?”

“Fine,” I say. And this time I mean it.

I saunter slowly back out to the car. Mother has her nose buried in a book. I pull open the door.

“Hi,” I say.

“How was your session with Dr. Howell?” This is Mother’s follow-up question after every session.

“Fine,” I reply with a little bit of judgement in my voice as per usual. This is our routine, our jingle that never changes. I hate when Mother asks. I don’t know why she bothers. I never say anything other than “fine.”

“Do you feel more connected to yourself?”

“Sure.”

“What about your project? How’s that going honey?”

“Fine.”

“Dr. Howell tells me you should be working on it a little bit every night.”

“Yeah, Okay.”

“When we get home, I’ll dig up a few of the old photo tins and you can look through them and-”...

“Okay, Mother. Please.” But I know she’s right.

I retreat back to my ugly yellow room and sit in criss cross applesauce on the floor, like a kindergartener. I stare at the stack of antique metal boxes Mother has placed in the corner of my room. In early Autumn, Dr. Howell assigned me a project: to make a scrapbook including photographs that are anxiety triggers for me. I’m supposed to write what I remember about the day the photograph was taken and what about it unsettles me. Now it’s late January and I haven’t touched a single photograph. I don’t know what’s changed today that motivates me to try for once.

After what feels like an eternity of waiting, I drag the tins over. They scrape the floor. I pull open a rusty lid with force and with a loud clang, it collides with the hardwood. I leaf through the photographs for several minutes, but one catches my eye. I cautiously pick it up. The photograph is of me standing out in the garden. Back when the garden was more than just overgrown weeds. I couldn’t have been more than seven years old when it was taken. I wear a serious expression and stand pin-straight with my skinny arms glued to my sides, the corners of my mouth turned slightly downwards. My attitude and stance are not that of a seven year old. It seems almost wrong in contrast with my skimpy pigtails and frilly ankle socks. I don’t remember ever owning those tiny white socks nor ever wearing my hair in pigtails. This sad little girl can’t be me. I feel my heart skip a beat as I notice our house in the background of the photograph and the tiny attic window in the corner. My heart-rate gradually increases, and then it starts to race uncontrollably. I feel hot. I walk around in fast circles and eventually I sink into my bed. I let my mind search for what it’s desperately trying to find. The panicky feeling lasts for no more than five minutes and then I start to feel myself drift away from my body. All I can see is a house. And an attic. I know the attic. I need to know what’s in the attic.

I quickly strip off my ratty tshirt. I’m unsteady as I walk to the bathroom. I don’t know why I’m scared to look in the mirror, but I am. Finally, I peer at my reflection. The harsh fluorescent lighting of the bathroom exposes my every flaw. The girl staring back at me has pasty, sallow skin, an acne pitted face and wispy brown hair that’s starting to grease up at the hairline. There are patches of peeled skin under her rib cage and traces of fingernail marks. She slides open the frameless glass door of the shower with ease. I swallow against my dry throat and stand in the shower naked and shivering. I think about turning the shower on, but I’m hesitant. Then I watch her twist the shower handle and await the inevitable rush of water.

My pruney fingers comb through a wet mass of luscious locks and I slip out of the shower. I don’t need to glance into the mirror to know I’m beautiful. The beautiful protector of the house. Not her house, our house. The house that Mae and I live in. I dry off my wet skin. If my skin is dry, maybe Mae won’t think of the attic. Water is one of the triggers that makes her want to unlock it. That’s why I had to help her.

I don’t bother putting on clothes. I don’t need clothes to hide underneath. I am beautiful and I am strong. I’m strong because I need to be strong for her. I’m not like Mae. Mae is weak. She is weak, and that’s why I need to defend her. That’s why I am the protector of the house. Our house. I walk steadily to Mae’s room and find what I’m looking for. The photos. I tear each one up into pieces. Pieces and pieces. So small, so she’ll never have to look at them again. I am worried for Mae. I worry that she’ll stop letting me in. That can’t happen. I know she wants me gone, but she needs me. So, so much.

I’ve been protecting Mae since she was four years old. I was strongest then, when she was smaller and weaker, but she’s been struggling lately. She’s resisting me. She wants to go to the attic now. She used to never want to go, and I hate that she wants to go now. I hate when she talks about the attic. She mentions it more and more these days, so I have to punish her constantly for putting me on edge. Scratch her until she forgets. Scratch her. Scratch her. Scratch her. Scratch away the attic. It’s my responsibility to keep the secrets locked away. I can’t let her in now. I can’t let her know. Not ever. I could let her in the attic, if I chose to. I could show her. But I don’t, because If I did, she would break.

I lay cold and naked in my bed. My mind hypnotized by the slow, rhythmic drips of the faucet. The faucet that seems to drip eternally. The distinct plop after plop of round droplets colliding with the cold hard marble of the sink. Echoing into the empty night. I don’t know how long I’ve been here, I don’t remember why I’m not wearing clothes or when I got in bed. All I remember is the house and the attic and all I hear is the dripping of the faucet. The faucet that I know, I know, is dripping with unbearably cold water.

The house and the attic. I concentrate. I try to remember harder than I ever have. I can see myself unlocking the door to the house. The house. The house. The house. What house? My house? My body. My mind. My soul. My house. The attic. My attic.

Not your attic.

My attic. Why do I only see it now? Where was it before? Why am I not allowed in the attic? Do I even want to go in the attic? I think I do. But I don’t know why.

You don’t want to go to the attic.

But I do.

But you can’t know.

Go away. Go away. Go away. What can’t I know? Who are you? Cold fingers pick at my raw skin. Whose fingers?

I can see they’re my fingers. I’m watching them, those are my skinny fingers peeling off a layer of skin.

Why am I watching this happen? Why am I doing this?

This isn’t me. This is a girl. I am not this girl.

I am this girl.

You are this girl. I am this girl. The girl in the house. This is why you can’t know what’s in the attic.

But I’m ready. I’m ready to know.

You’ll never be ready.

The drip drip drip of the faucet. The dark dark dark of the night. I feel it like I’ve felt it before. Like I have so many times before. I feel it.

The rough skin, my pruney fingers, the neverending rush of cold water.

The rough skin, my pruney fingers, the neverending rush of cold water.

The girl is me?

Then I start to cry because I know what’s in the attic.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.