All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

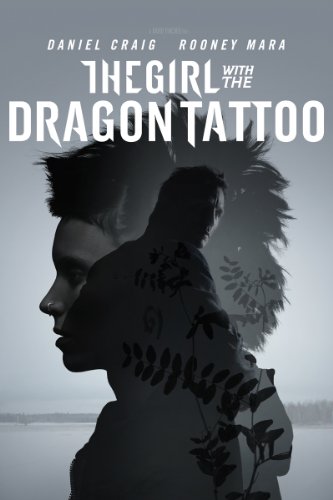

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011)

Her eyebrow is pierced. So is her nose. So is her lip. And so are her nipples. Her eyes are sinister. Her face is as cold and sharp as the winter wind in Sweden, and she is the female heroine equivalent to one of those inexplicable cultural zeitgeists that somehow sweeps nations the world over. Lisbeth Salander, the intense, almost punk-like female protagonist of the best-selling Millennium Trilogy by Stieg Larsson, is reincarnated in David Fincher’s own adaptation of the first novel in the series, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. No, Fincher’s film is not a remake, it is a re-adaptation. Many questioned the point of making an American version of the Swedish film (which they spoke about erroneously), and without Fincher, there would have been no point. Though overtly a mainstream exercise in sadomasochistic filmmaking, it would have been nothing without David Fincher’s distinct brush strokes on the film. It unavoidably draws some comparison to the Swedish incarnation, starring Noomi Rapace, but it is best to think of it as an entirely separate entity. As aforementioned, this is a re-adaptation. And it is one hell of a re-adaptation at that.

Disgraced journalist Mikael Blomkvist is called upon by the wealthy patriarch of the Vanger family to find the murderer of his dear great-niece Harriet. The cast of the Vanger family is like if you put Wes Anderson’s Royal Tenenbaums into a Swedish horror film and gave them hard liquor. At the same time as Mikael begins his search for Harriet’s killer, damaged hacker Lisbeth Salander is trying to make ends meet when her caretaker suffers a stroke and she is, once again (it seems) deemed incompetent, unable to take care of herself, and in need of a social worker. As the two storylines intertwine and cut from one to another, Mikael and Lisbeth eventually team together to create a bizarre Mulder-and-Sully-esque relationship.

It is difficult to shy away from comparison between Fincher’s film and the Swedish film from 2009, so I shall keep it short. In essence, the two are not comparable at all. Yes, here and there, you find various things to compare, mostly because they are based on the same story, but the two films offer very different experiences. That is honestly the most one should say if one is forced to compare the two: they are different films and offer different experiences.

Fincher’s film is distinctly Fincher-esque. From the slow tracking shots outside of a door with the sounds of a wailing young woman, to the scene composition of two men and a snowy outside chat (medium long shot showing the sides of both men with the door to a luxurious house in-between), to the yellow-green color palette of the past (as in the 1950’s) and the past (Lisbeth and Mikael’s past, being their former jobs and interiors of their jobs); it has David Fincher written all over it. It is this unique and singular style that separates the film from its Swedish counterpart. That is not to say that the Swedish film is not stylistic at all; it just was not directed by David Fincher. Rather than employing the same kind of kinetic energy from Se7en and Fight Club, or the romantic style of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, the style in Dragon Tattoo seems more languidly paced and thoughtful, almost as gloriously lucid as his film Zodiac. Though, Fincher has honed his skills since then, and it seems far more polished. Granted, as polished as it is, and perhaps because of the film’s inherent mainstream nature, it is not Fincher’s best film. Unique and inventive to a point (as much as you can be with such a sprawling story), it just is not his best. It is plenty excellent, plenty enthralling, but not his best. And I hope he is fine with that, because this film is far from a waste of time.

When speaking about how the Swedish adaptation and the Fincher adaptation offer two unique and different experiences, I mean, primarily, this: the Swedish version is a long, drawn out, sprawling, and epic mystery procedural film. It sifts through evidence and suspects like the best episode of any procedural drama on BBC. The American rendition, however, offers elements of this but seems to ruminate more on the basis that it is a character study. It concentrates and focuses its energy on Daniel Craig’s Mikael and Rooney Mara’s Lisbeth. The film digs deeper into both characters’ psyches and motivations, and does so in the most expert way; the only way that David Fincher would allow it. You can think of his previous films as character studies as well, films that examine closely the actions of their protagonists with a Kubrickian microscope. And what Fincher and screenwriter Steve Zaillian observe is satisfying and a little bit unnerving.

Enter Mikael Blomkvist, a journalist sued out of his brains for libel, and thus running away from his demons. He is, as Salander says to the man who hired her to do a background check on him (for the sake of the Vanger family, who would then employ Blomkvist himself), “He is who he presents as.” But, of course, he’s a little more than that. The affair he’s been having with his co-editor has broken his family and thus his relationship with his daughter is fractured, and then fractured even a little more by her interest in going to a Bible camp. He is not an Atheist, he is a journalist; a man who has seen and written about far too much evil within the world (mostly corporate evil, we are led to believe) to acknowledge anything else than the written word of an honest reporter. Daniel Craig, who may be most recognizable to some as Bond, James Bond, sheds that suave exterior in place for a more hardened kind of character. Though, Craig seems to be still adjusting to this kind of procedural mystery story, almost as if he is not quite used to the feeling. Nevertheless, he does play the part fairly well, a part which requires him to be anything but that British spy. His look, a mix of seedy yet rugged handsome, fits Blomkvist in that he is the kind of man you want to trust, but would find yourself having a little trouble doing so at first.

And we have our heroine, our unorthodox hero, Lisbeth Salander. She has many holes in her body, and not just the physical kind. Maybe a little brutish and barbaric, she is not familiar with a constant state of happiness. The fact that she has a checkered history is written all over her. She does not wear this fact with pride. She wears it with the same kind of demeanor that one of her shirts reads in the film: “F*** you, you f***ing f***”. She does not give a damn, clearly. Or maybe she does. What I like about Rooney Mara’s performance is that she it is able to embody the coldness and harshness of the character that is obvious and, maybe, overstated to a degree. But she is also able to tone that part of the character down a bit and fit in a sense of vulnerability. There are moments in the film where her defense is down and where she honestly looks like she has been hurt, both physically and emotionally. Even with the cost of probably getting kicked in the groin, you kind of just want to give her a hug. There’s a fragility, an angelic quality behind the piercings, strange hair, and layers of makeup. This is who she is now, and she may have created it for herself as an escape, but Mara’s beautiful and intense performance makes it more evident that she was not always this way. (Luckily, this lovely performance is a completely different taste from that of Rapace’s. Something akin to pierced apples and pierced oranges.) The androgyny of the character is a fascinating aspect of the film. She does not look too polished or Hollywood as one may have feared, and the cheekbones Mara has allows for a complete transformation. Mara takes on the role with force and dignity all the while, and her emotional acumen for the character is deftly shown in the film at all times. In short, yes, I do think she deserved her Academy Award nomination for Best Actress.

The look of the film says Fincher. One may note this is the second film in a row that David Fincher has done that features heavy typing. The interiors are mostly sparse and immaculate, with the interior lighting reflecting either a cold blue or a stinging yellow, both of which are reminiscent of the look for The Social Network. Jeff Cronenweth (who has worked with Fincher previously on Fight Club and The Social Network) takes the sterile and frigid motif of immaculate, minimalist space and applies it to the film. The shots are marvelous, going back and forth between the grotesqueness of Lisbeth’s lifestyle to the perfection of the Vangers. Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s score is frighteningly good, utilizing techniques that, for better or worse, send shivers down the audience’s spine.

Regarding the brutal and much talked about rape scene, I found the techniques used quite fascinating. It is one of the most viscerally harrowing scenes I have watched in ages, at once repulsive and yet captivating. What David Fincher does here is he makes the scene at times explicit and graphic and at others, completely suggestive. It is in these suggestive moments, where sound design plays a critical role, that the film becomes most uncomfortable and unpleasant. Because the viewer is unable to see “everything” as it were, the worst is left to the imagination in the same way that the absolute worst was left to the imagination in the castration scene in Hard Candy. Playing with facial expressions, sound effects, and musical score is the way to be completely sadistic to your audience, and it is done in grand fashion. Fincher, though, does not allow the audience to revel in these moments. One step and one cut at a time, he does not linger. Which makes the audience question which would be worse: the cutting away from expression and sound from one to another or if it would have been worse to have it linger on one long shot for the entire time and witness the entire thing like a fly on the wall? I am most satisfied (or at least as satisfied as one can be during a scene like this) with Fincher’s interpretation.

The main title sequence is extraordinary. Using visual motifs from the film, Lisbeth is projected in animated and oily glory, with wasps coming out of her pupil, the Dragon Tattoo she has on her back coming alive, the phoenix of her soul bursting into flames, many a USB cord throttling her, and the horror of male assault being suggested at various turns. It is a brilliant title sequence, one that pretty much sums up who Lisbeth is as a person/character. Reznor and Ross’s cover of Led Zeppelin’s “Immigrant Song” plays during this, with the Yeah Yeah Yeah’s Karen O on vocals, and it screams and wails, almost as if Lisbeth herself were singing. The song fits, though I do not know why. The cover employs a much more electronically manipulated sound, and that seems to fit the theme of the film. Lisbeth is a harbinger of death, angst, pain, and fury, just as the song seems to suggest.

David Fincher’s vision for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is an interesting, unrelentingly ferocious film. It combines the book’s languid, slow pace but includes the brutality of the characters and their psyches. Rooney Mara makes a star turn as Lisbeth Salander, a performance that is able to show both the character’s fury and fragility. While it may not be Fincher’s best work, it is nonetheless an example of his ability as a director. Here, Fincher directs a film as multifaceted as its female protagonist. Sinister, damaged, pierced, fragile, and fantastic.

Grade: A-

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.