All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Cutting Carbs MAG

Take it away from me! I’m being soooo bad! I just can’t resist! Whether it’s my mom, dad, sister, or friends, I constantly hear these phrases while sitting at the dinner table. The waiter takes our orders, brings our drinks, and what comes next? Almost always, they bring a complimentary gift: whether it is focaccia sprinkled with rosemary, slices of a fluffy baguette, or buttery garlic naan, bread is the perfect pre-appetizer snack. The question is — will I eat it? When I’m with my family, my mom will shy away from the forbidden basket, watching intently as I take a bite. If I’m out with friends, thoughts race through my mind as the petrifying platter arrives: Who is going to take the first piece? Is anyone going to eat it at all? If someone does take it, how many bites will they have before pushing it away, shrieking that they’re “so stuffed” after one bite? The fear of eating bread is a real one, and it seems impossible to escape because of the ripple effect it creates. This isn’t just the case with bread, though. It’s all carbs — bread, rice, potatoes, and pasta, to name a few — foods that we often label as “bad” or “special treats,” foods we don’t eat unless we’ve “earned” them. Cutting out this food group is promoted: common, normal, healthy.

A basic Google search tells you that “carbohydrates are your body’s main source of energy: they help fuel your brain, kidneys, heart muscles, and central nervous system.” Carbohydrates are essential to the human body, so why are we so afraid of eating them? In the past decade, eating a low-carb or “keto” diet has gained an immense following, further stigmatizing eating carbs. Before it gained popularity, buying rice at the grocery store was as simple as white or brown. But now, the grocery store aisle is overwhelming: rice made of cauliflower, pasta made from chickpeas, bell peppers instead of burger buns — any “healthier” options people can think of. Even if you’re not on the keto diet, there’s a sense of guilt walking down the aisle: I should buy the cauliflower rice instead, shouldn’t I? I should be more healthy. You give in to the substitutes, convincing yourself that they will taste just as good (spoiler: they don’t) and that the real pasta, or rice, or bread, is in fact bad for you — exactly what the diet industry wants you to think. This surplus of low-carb options puts pressure on us to feed into the latest diet trends. This isn’t the first time this has happened, though. The wheel of diet trends is constantly turning: Atkins in the ’70s, fat-free in the ‘90s, Weight Watchers in the early 2000s, and now, a keto craze. As the cycle of dieting repeats, restricting different food groups becomes more and more normalized.

Today, I see promotions of keto everyday in grocery stores or on TikTok and Instagram. This wasn’t a recent discovery, though; I first learned about keto at a young age—the summer going into fifth grade. During the summer weeks we spend at my grandparents’ house at the beach, my dad can always be found reading on the porch. One day that summer, I immediately noticed that he wasn’t holding his usual New Yorker magazine, but instead a thick book with a laminated green cover, plastered with images of vegetables surrounding big white letters that spelled K-E-T-O. I soon found out that my dad was going keto (whatever that meant) in an attempt to lower his blood pressure. I was genuinely shocked for a few reasons. One, I was horrified that my dad couldn’t eat frozen bananas, our favorite summer treat. The other reason, though, was more extreme. As my dad read his green keto bible, I realized that dieting was not something exclusively for women. My mom, and other female figures in my life, never went on diets when I was growing up, so why was I confused to see a man doing it? This confusion is no coincidence: the dieting industry is directly targeted towards women, and my perplexed 10-year-old self proves it.

While thinking back on this, the gravity of female dieting culture has come crashing down onto me. At the grocery store checkout, it was never a man on the cover of Shape magazines — it was a woman with a tape measure around her waist. Growing up, I watched thin women in commercials choose cake-flavored yogurt over the real thing. When watching “Mean Girls,” I didn’t question it when Regina, Karen, and Gretchen all pointed out their insecurities while standing in front of a mirror. Agonizing over your appearance, and dieting as a result, is a rite of passage for young women in our society: we’re told that we’re never quite good enough and need to go to extremes in order to achieve perfection. At 10 years old, I had already picked up on these messages from the media — they are almost impossible to avoid internalizing at a young age.

In the climate of modern day society, these commercials and movies would be questioned or canceled, so it’s easy to think these ideas are gone. In reality, they are just reincarnated on social media. On any social media site, it is so easy to compare yourself to others and fall into dieting and exercise traps — posts that encourage behaviors like cutting out food groups or counting calories. On TikTok, there is a whole genre of videos called “What I Eat In A Day,” where users (mainly women) film what they eat, which is sometimes not much at all. Every once in a while, videos like these are fine. But once you like one video, follow one user, or click on one link, these videos will take over your feed. These ideas spread faster than they ever could before, and target young girls long before they are teenagers.

Social media that promotes dieting, over-exercising, and an unrealistic beauty standard is easy to be roped into — just like diet trends are. It’s the same sense of guilt as the cauliflower rice in the grocery store: I should like this post. I should be healthy. At 14, I fell into this trap: videos of girls 10 years older than me talking about their diets, workouts, and so called “wellness.” My whole feed became filled with these videos, to the point where I thought barely eating, analyzing everything I ate, and over-exercising was normal for someone just entering high school. Realizing that these behaviors aren’t normal has allowed me to grasp just how diet-focused our society really is. This feed didn’t disappear overnight — I had to stop interacting with these videos for them to go away. It took strength to unfollow, unlike, and attempt to unlearn everything that social media told me was healthy. When ideas and behaviors are directly targeted toward you, it’s hard to shy away from them without feeling badly about yourself. Every once in a while, a “What I Eat In a Day” video will pop up as I’m scrolling through TikTok. Now, two years later, I have the control to click the “not interested” button.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.

I'm a 16 year old girl living in NYC!

The goal of my essay is to make readers reflect on the way unhealthy habits are often promoted as “healthy” in our everyday lives—whether it be through media, family, or friends.

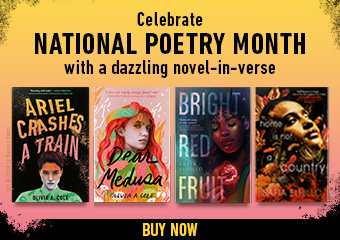

Also, a side note--the image I included is from the "Mean Girls" scene I reference in the essay