All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Durgapur, the Indian Subcontinent, or Perhaps the World Itself

We, humans, associate ourselves with many things: another person, a society, a country, a club, a phone, or even a key ring. This primitive instinct gave rise to cities, civilizations, and nations. Since its advent in the nineteenth century, nationalism has become entrenched in people’s mind and has caused conflicts from minor skirmishes to catastrophes: history stands as brazen evidence. While nationalism can be an impetus for humanity to work together, it is a curse that rips humanity apart. Although nationalism has brought “pride” and “glory” to many, in particular to those who serve in the military, it has caused genocides, looting, and imperialism to engulf the lives of millions around the world. In spite of once being a moderate nationalist myself, I have turned toward a more enlightened path, toward a more global perspective on our existence.

It is hard to understand why such a “unifying” force as nationalism would divide people to such great extent. After all, nations are like big families, they bring people together. We love our country and will die for it” is a common patriotic utterance, just as we might die for our family. However, we may fail to understand that the borders on maps are just arbitrary lines drawn by politicians. Patriotic persons face a dilemma at their nation’s border: someone who lives two meters beyond the border is a foreigner—even if that someone is a relative. Does not this sound absolutely absurd? It’s like a game: we associate closely only with those who live inside the border, while anyone outside it is “an alien,” “a foreigner,” and whatever pejorative terms they are assigned.

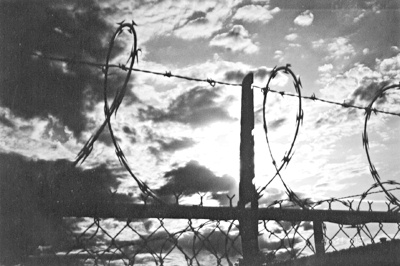

Do not get me wrong. Nationalism is healthy to a point. It is easy and almost natural to feel associated with the people of one’s own culture; however, it is the technique through which nationalism is implemented in our lives that annihilates its nutritional value. It creates walls of fire that demonize other people. While nationalism strongly unites people, they usually unite against something. Nationalism, then, divides humanity into various groups, which stand against each other. The other group frequently appears evil in the ominous shadows created by the fire of hatred. The government of each nation initiates policies that instill this fire in the hearts of the children, which they cherish and protect throughout their life. A piece of colored cloth and an animal are seen as almost “sacred” symbols of a nation. People pledge allegiance to the cloth and to a republic 99.99 percent of the population of which they do not know, yet “associate” somehow with. They even give their lives and take others’ lives in a frenzy of war to “protect” the nation’s interest. Well, it does not hurt much to kill an alien, does it?

Well, it does! Born in Bangladesh, where culture is fairly homogeneous, I experienced an extraordinarily multicultural childhood. When I was six, my family moved to Beijing; when I was ten, I started taking Arabic lessons, and being born in Bangladesh, which until relatively recently was part of India until 1947 and then Pakistan until 1971, I inevitably became acquainted with Indian culture as well. Seeping Western cultural norms also became part of my life as I grew up, because of the historical British influence in the region and the importance of English internationally. Brought up in such a multicultural childhood, I realized the values of all cultures to an extent, but my realization fully bloomed the summer I graduated from high school, when I visited my ancestral land of Durgapur where my great grandfather lived. Durgapur is a tiny village in eastern Bangladesh. The day my father and I reached Durgapur by car, it was almost like a celebration. Kids flocked in tens and twenties around the car, as if it were a UFO. I laughed as the kids reached out to touch the car’s gleaming white metal, eyeing it with googly eyes, running along beside and behind it, and my dad screaming the whole while in Bengali, “Get away! You will get hurt!” But who listens when they have a slow moving UFO in front of them?

When we finally got out of the car, half the village knew that someone from the city had come. This was my father’s childhood place, and he started talking with his second cousin in an accent I could not decipher. I felt like the ugly duckling, or like an exotic animal in a zoo: everyone kept staring at me as if I were an instant miracle in the creation of the universe. Even when I stared back at them, they did not stop their staring; they kept looking until I looked away in embarrassment. When I complained about this to my dad, he said, “The villagers are just intrigued by the city folks. They do not think it’s rude to stare. They are just…um…they just think differently.”

That “think differently” phrase struck me. Later, when I went to have lunch with my father at his second cousin’s house, who lived in a tin-clad cottage, with only two rooms—one bedroom and a drawing room—the phrase nudged me again. How can the people I see in the city be so different from the people who are living in the same country but in the village—their perceptions of reality and bliss are so different? While some people are unhappy earning millions every year, here people are running on probably 3000 or fewer dollar. Here, my third cousin (who is about four or five) is happy dancing naked in the rain, ignorant of the technological world, while I am sometimes frustrated how tiring my own “advanced” life is, when apparently I have everything they could wish for.

My own relatives are different from me, so what about all the rest of the people in the world? It seems obvious that they will think differently. Happiness, sadness turns into relative states of mind then. However, we have one intrinsic thing in common: we are ALL humans; naturally, we are united. Unfortunately our instinct of association pushes us away from natural empathy and drives us in hordes toward nationalism. This happened when Lord Mountbatten, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah decided to divide India into pieces—a “Hindu” piece and a “Muslim” one! Hindus and Muslims, who were neighbors the day before, were suddenly foreigners in their own lands, where they were subject to persecution and harassment. And why was that so? Simply, because the politicians declared it. Hundreds and thousands of Hindus and Muslims were murdered after the “independence” of India and Pakistan, all because of this mentality that “this land is ours and they (Hindus or Muslims; depending on which side we are on) came into it.”

Actually, these they’s are not the problem here; the problem is the mentality. When we segregate our own kind, we cultivate nothing but hatred. While transcending these “natural” cultural and national identities is hard to do, it is important in order to extinguish the fire of nationalism. Building a brilliant flame, the fire obscures the hatred that is its fuel. It feels safe and warm for a while in the light. But if we get too close, it can burn our flesh just as easily as the fuel that went into it. And if it increases in capacity it can grill the “enemy” all right, but it can disintegrate us into ashes as well.

Although nationalism in moderation ideally can unite people, unfortunately in most cases it does not. Rather it obscures judgment about our government’s actions and leads us to label people and generate stereotypes that beget social prejudices which only add fuel to the fire. How many instances can we think of in which a “patriotic” person stood up against their nation in order to stop the horrific deeds its military committed in foreign lands? Virtually none, because patriots are defined as supporters of the nation. If one is patriotic and their nation decides to oppress “foreigners,” would it be more appropriate for them to support their nation, or those who are being oppressed? Well, I do not know the answer to that but I do know that the oppressed are of the same species as the oppressors. Labeling anyone because of their geographical location is perfectly fine, but believing this as a natural distinction or natural hierarchy makes the guns shoot and the cannons fire.

Different are the cultures in the world: the English eat with silverware, the Indians and the Arabs eat with their right hand, the Chinese eat with chopsticks, and some may even eat with tree twigs, and yet we all eat. Different does not necessarily mean wrong; different means alternative lifestyles, thinking processes and habits. Having these differences, we are basically the same. We live in the arbitrary world of artificial languages and boundaries that are created for smooth governance of seven billion people, and we should leave those boundaries and languages at that. They define us, but do not make us better or worse than the other cultures. Multifarious languages in the world make us ponder on the creative power of the human mind, but they should not be used to wage war of humans against humans and to refuel the fire of hatred. Rather we should let these differences make us realize that there are people like us in parts of the earth who have “eccentric” cultures and perspectives just as we do. Cultures and nationalities exist so that humans can identify with each other, and they certainly should not exist to alienate them from the us. Otherwise, humanity’s downfall will come too soon.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.