All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

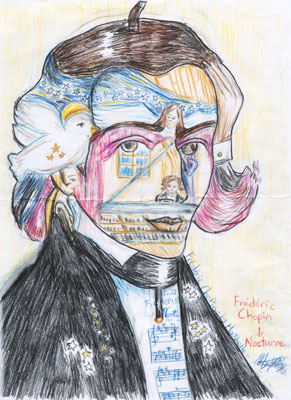

The Piano Man

The rustic piano was the first instrument of its nature to grace the small town of Anatevka. Before its arrival, the percussive clanging of picks in the mines, the whirring of the old spinsters’ wheels, and the occasional bleating of sheep served as music for the town’s humble residents. Despite the piano’s placement in the tavern, a bureaucratic decision that perturbed the pious, the sound that drifted from the boxy, splintered, yellowed thing beckoned the worn to abandon their worries, fears, and more pressing engagements to briefly dedicate their souls to a few measures of bliss. The sound by no means was beautiful or worthy of a trained ear, but it was glorious enough to muffle the daily cacophony of poverty, illness, exhaustion, and anxiety. Chipped keys, stuck pedals, and warping wood were of little concern to anyone but the player, a man tainted by beauty and symphony that the people of Anatevka had never seen or heard: wealth, good fortune, and fullness of the stomach.

He was eager to spend, but reluctant to earn. Giving from the heart was inconceivable to the piano man, as it would require him to forfeit his coin purse or mop off his brow. He never held a real job, a backbreaking, monotonous task; he only knew the world from the bench of a piano. The price of his music, a rare luxury, was of extreme expense to the people of Anatevka. The man required three square meals every day, payment at the end of each shift, and lodging, commodities that most of the townspeople lacked. Being the only accessible musician had its perks, perks that the piano man was too blind to see and too careless to refuse.

For the people, he played tunes that even a simple-minded amateur could master within a week. For himself, he played the most heavenly compositions known to man, the kind conceived by geniuses with the aid of the muses themselves, but only after hours did he play such wonders. Foreigners pestered him throughout the day: “Can you play it again?” or “God bless you and keep you, sir,” and so on. The night was his time. He was Sasha Tsorkotev, a musician: failed and unappreciated. Only after Sasha emptied his heart did he retire to bed.

The townspeople never spoke ill of Sasha because of his gift; they heard the music in the night and knew that the piano man could rival the angels and their harps. They wondered how such a blessed man could be so bitter and cold, and no one dared confront him for fear of driving him away. Only a little girl of six years was brave enough to face the miser.

The clunking of thick-soled boots pounded in Sasha’s head, throwing off his internal metronome, turning what was meant to be a lovesick ballad into lively reel. Furious, he searched for the source of the retched tapping, but everyone at the tables behind him was stoically waiting for him to continue. As he turned back to the ivories, a little voice peeped, “Keep going! It sounded much better that way!”

“Who said that?” roared the Piano Man.

“I did.”

A little girl stepped out from the side of the piano. How long had she been standing there? Did she know who he was?

“No. It sounds much better slow. If you can play, you can criticize me,” with that he turned back to the keys. Who was she to judge?

“But it sounded so sad. You always look so sad when you play…I’ve seen you cry some nights. I thought if you played something happy, you’d look a bit happier,” declared the critic.

“Like I said, girl, only talk to me if you can play,”

“I can try, but I’m not good like you.”

Taken aback, the piano man made room for her on the bench and watched as she tried to make herself comfortable. She rolled her shoulders back, puffed out her tiny chest, and gently placed her stubby fingers on the keys; her form was impressive for not being properly trained. First, one tap of her index finger wrought a C out of the beast. Then her fingers fluttered over the keys, striking each one with passion, tapping out one of the most innocently beautiful melodies he had heard in his lifetime. Even when her fingers slipped and struck a discord, the piano man could not bring himself to stop her. In fact, he accompanied her, throwing in harmonies and intricate counter melodies. It was then that she stopped playing.

“Why did you stop?” he inquired, baffled by the abrupt silence.

“I wanted to listen to you play,”

“Well I was listening to you. Where did you learn to do that?”

“You.”

“Me?”

“I watch you play every day, even at night. Sometimes, I can’t follow your fingers though.”

“I never played anything like you did, so where did you hear it?”

“My head.”

“So what do you call it?”

“I call it, Song for a Fallen Angel.”

“Who is the fallen angel?”

“You.”

It struck Sasha that he faced a fate worse than a fall from grace; he suffered from ungratefulness, a condition that deprives the victim of the fruits of existence: joy, peace, contentment, and feeling. The girl would not just be his new prodigy, but his savior from himself. Some might call her a guardian angel.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.