All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

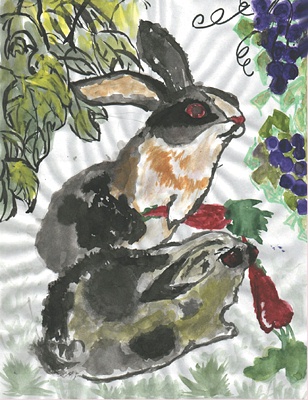

The Rabbits

On a white-skied day late in April, Harold J. Whittaker called in sick to work, deciding that he needed a quiet day to himself. He awoke from a deep sleep at 8:30 AM, an hour later than he usually got up to go and work at the bank. Standing up from his bed and stretching his seventy-three year old body, which erupted in a symphony of cracks and pops and aches, Harold smiled at the button-down shirt and dress pants that would remain in his closet for the rest of the day, untouched by fresh sunlight or brisk air. He grabbed his thick plaid bathrobe and wool slippers and padded softly down the stairs to breakfast.

Harold lived alone. He had always lived alone. He had had some girlfriends in college and in his early years at the bank, but they came and went without much excitement. He thought of them as interesting landmarks on the side of the highway that one might view through a car window during a long drive. A tree in burning fall bloom, a rock formation shaped like a goose, a sunset disappearing over a hill. They were pleasing to look at for a second, but looking too long made you dizzy and confused. Harold found he was often dizzied and confused by women. So he let them pass him by.

Harold’s bachelor status went totally unnoticed to him for a good portion of his life. He remembered only a single moment of clarity wherein he looked around, heard the white noise of silence bounce off the walls of his living room, and wondered how he had gotten where he was. This was just life, Harold thought to himself. I guess this is how it’s supposed to be. I went through life and I just ended up like this. Harold thought no more of the subject after that moment, pushing it forcefully behind a heavy door in his mind and locking it shut.

After breakfast, Harold decided that he would go into town and run some errands, taking deliberate care to avoid the block that contained his workplace. After the supermarket, the dry cleaners, and the shoe store, Harold turned into the drugstore, which was surprisingly busy. The fluorescent lights shone just as white as the sky outside, only slightly more menacingly. He picked up a small red basket and started meandering through the aisles. Office supplies…bath and body products…pharmaceuticals…

The next aisle Harold turned down was full of half-priced Easter decorations. It was a wonder, Harold thought, that they hadn’t tossed these things the very minute Easter was over and replaced them with beach balls, sand shovels, and all other sorts of ridiculous things that came prematurely to their respective season. He walked past cellophane baskets full of enough candy to give a child instantaneous diabetes, fluffy plush chicks coming out of eggs, rabbit-ear headbands. At the near end of the aisle, right at eye-level, were two small ceramic rabbits. Harold got exactly four steps past them before he stopped and turned around. He walked right up to the two little rabbits and halted.

His heart stopped, and for a second he thought he had been struck by lightning. A vacuum opened up inside his chest, and he felt as if everything in the world had been sucked away except for him and these two little rabbits. They sat so delicately on the shelf, side by side, and Harold thought he could hear sweet-tasting whispers pass between them. They were looking at him expectantly, he thought. They were waiting for him, resting on their smooth haunches. He felt them scrutinizing the weight of his body, poking around inside the wrinkles on his face, swishing their tails against the contents of his weary mind. Harold swallowed hard. He wanted to engage them immediately in conversation, but knew he needed to proceed delicately. Like a gentleman. Like a good-natured friend. He put his hands on his hips. He examined the rabbits closely, trying to imprint their images on the gray matter of his brain like the world’s most important stamps.

One rabbit was white, and one was brown. He noticed quickly that both were female - they each had sweet little black eyelashes and a bow placed delicately between the ears. The brown rabbit’s bow was yellow, and the white rabbit’s bow was pink.

“Hello Celia,” said Harold to the white rabbit, bowing just a little bit and smiling, “and to you too, Dolores.” He repeated the same gesture for the brown rabbit. “You ladies look so lovely today. I hope I haven’t interrupted your conversation.” He paused, listening for a response. “Oh yes, well, I thought I’d, you know, play a little hooky today. I hope neither of you will rat me out for it!” Harold winked. The rabbits were still. Then his face shifted, became tentative, almost embarrassed. He looked down the aisle as if he thought about making a hasty retreat, but then turned back to the rabbits and issued a phlegmy throat-clear. “I was wondering if maybe you two would like to join me tonight for dinner. Nothing special, really, I just…oh no, Celia, I’m not the kind of man that tries to date two women at once! Don’t you worry about that. Don’t listen to her, Dolores, I wouldn’t want you to get the wrong idea about me. Anyways, would you want to come over? I’m just about done with my errands, and well, you know I’m off for the rest of the day…”

Despite the peculiarity of an elderly man talking to two inanimate rabbits, no one seemed to pay much attention to Harold. Although his gaze and gestures were clearly meant for the shiny little black eyes of the rabbits on the shelf, many of the other customers assumed him to be talking on a hands-free telephone device, and passed him by quickly with little more than a quiet “excuse me, sir.”

The rabbits had apparently agreed to Harold’s request, for he soon placed them very gently next to each other in his little red shopping basket and headed for the register. There was nothing else in the basket, because Harold had completely forgotten whatever he had initially come to the drugstore for. The cashier was an impatient teenage girl with enormously long fake nails. They scraped against the ceramic of the rabbits when she picked them up off the counter, and Harold winced as if in physical pain. The girl put Celia and Dolores into a plastic bag which Harold promptly snatched up, glaring at her.

When he arrived back at his house, he noticed his neighbor Olive stepping outside and heading towards her mailbox. He quickly tried to un-notice her and speed up his pace towards his front door. He was not quick enough. Olive’s chihuahua, King Charles III, had come bounding into the yard beside his owner and starting yapping shrilly at Harold. Olive turned at the sound of the barking, and flashed a gummy, fuschia-lipped smile at her neighbor.

“Hello Harold!” she yelled and waved. Olive was younger than Harold, in her early sixties, fairly plump, with dark brown hair that seemed to have an iron will against turning grey. She seemed to be perpetually cheery, which Harold attributed to her job as a kindergarten teacher. She was always trying to engage him in conversation. He remembered a particularly painful afternoon where he had stood by the fence that separated their two yards and listened to the tragic stories of King Charles I and King Charles II, both of which involved a large yellow Hummer driven by Mrs. Halifax, who lived at the end of the street.

Harold nodded politely at Olive, and tried to continue his journey towards the front door. He failed.“Oh wait, wait!” cried Olive, shushing the dog, who whined angrily at her feet. “How are you?”

“Im good, Olive, I’m perfectly fine.” The magnetic pull of Harold’s desire to get home was strong, but even stronger was the imaginary ball and chain forming around his foot with the big fat label of OBLIGATORY POLITENESS. “How are you?”

“Oh, I’m just beat!” she said, wiping non-existent sweat off her forehead with an exaggerated “phew!” She put her hands on her hips and the skirt of her dress rustled. “My kids really ran me ragged today. We had a little birthday celebration, and I explicitly told the parents not to bring soda, but of course they never listen to me about anything…one day I swear I’ll give the kids energy drinks instead of juice for afternoon snack, send ‘em home and see how their parents feel then…”

“I know how you feel,” said Harold, even though he had never endured a day full of screaming five-year-olds on a sugar high. “It’s been an awfully long day for me too, and I can’t wait to just get home and…”

“I didn’t think you got out of work until late!” Olive interrupted, but then quickly blushed and covered her mouth with her hand. “Oh gosh, I’m so sorry, I didn’t mean to sound like a lonely housewife! It’s just that I notice, that’s all. Charlie always starts barking when your car pulls into the driveway. I think he likes you!” Harold glanced at the dog, who had two front paws on the fence and was attempting to nip the plastic drugstore bag. He glared at the animal and wondered if maybe he might ask Mrs. Halifax if he could take that yellow Hummer for a test drive - to see if he wanted to buy one, of course. He took a deep breath before replying to her to build up his quickly dwindling social endurance.

“Actually, Olive, I wasn’t at work today, I was…” Harold couldn’t come up with a plausible answer fast enough. Olive caught on to the truth in his pause and ripped it right open with her laughter. “Playing hooky! That’s fine, don’t look so worried! I won’t report you to the authorities,” she giggled. “That’s what neighbors are for, right? Keeping secrets and hiding the bodies!” The joke made her laugh even harder. Her laugh, like her figure, was full, and her breasts and belly shook as she gasped and then put her hand delicately up to her mouth to control herself. “So what did you do on your exciting day off?”? “Nothing much. Just running some errands.” Olive looked down at the drugstore bag where Celia’s little white ear was poking out.

“Are those Easter decorations?” she mused, reaching right over the fence and picking Celia up out of the bag. Harold wanted to swat her fat hand away, but did nothing except fidget nervously. “Oh, there’s two!” and out of the bag came Dolores as well. “Why now? It’s way past Easter!” said Olive, holding the two rabbits up in front of her face and shaking them back and forth. Harold didn’t want to answer the question, nor was he quite sure how he might go about doing so. Luckily, Olive’s mouth cut off his frantic train of thought. “My kids just love rabbits. We had one for a class pet once, but God, was the poor little thing nervous. I remember…” And she launched into another tragic story of a furry life lost too soon. Right as Olive said the words “paper shredder,” Harold decided he could not stand being trapped in this interaction any longer. He snatched up Celia and Dolores, who Olive was using as props to tell her wild story.

“I’m sorry, Olive, but I’ve really got to go. I’ve got some things from the bank I want to catch up on at home…so I’m not too swamped when I go back tomorrow.”

“Oh, I’m sorry! I didn’t mean to keep you so long with all my talking. That’s just fine, Harold. But we should do this again soon, yeah? Maybe I could come over some time? And we could get a chance to really talk?” Her voice was warm and sweet and tinged with the slight bitterness of desperation.

“Sure, Olive. Soon.” Harold said these words almost robotically as he turned his back to her and finally, joyfully, headed for his front door. “Welcome, welcome,” he said to the rabbits as he stepped over the threshold into his living room, cradling the plastic drugstore bag carefully in his arms. He kicked off his shoes and set the plastic bag on the kitchen table, taking each rabbit out carefully. He placed them very gently on the mantle above the fireplace, so that they could have a view of the whole living room and the cul-de-sac outside through the large picture window. “I’m sorry I didn’t get a chance to clean the place up for you before you got here, but please, make yourself at home.”

Harold chatted pleasantly with the rabbits while he dusted and picked up stray magazines off the floor and attempted to scrub rings off the coffee table. He started to worry briefly about having asked them over for dinner, thinking about his cooking skills and how they had likely atrophied beyond repair over the years. He thought about asking them if there was anywhere special in town that they might like to go, but when he looked up at their glossy little faces he decided that it was probably best for the three of them to stay in the house. It felt more comfortable that way, Harold thought, and he knew Celia and Dolores would agree.

He cooked pasta with vegetables for the three of them, and was delighted to pull out two extra chairs from the hall closet to place at the dining room table. “I swear I never thought in my life I’d want to be a vegetarian, but you girls convinced me,” he said as he speared a piece of broccoli on his fork, “I’ll have to go tomorrow and pick up some more vegetables. Anyways, I’m glad you’re enjoying yourselves!”

After dinner, Harold and the rabbits sunk into the living room couch to watch a TV movie. At the end, Harold found himself welling up with tears, grinning like an idiot. He was briefly bewildered, because he didn’t think he remembered a single plot point of the whole movie. He couldn’t pinpoint why he was crying, which made him laugh. Swallowing the giggles, he announced to the rabbits that it had been an exhausting but wonderful day, and now it was time for bed.

Harold took the rabbits upstairs, one tucked under each arm. He left them on a small round table in the hallway while he took a shower and changed into his pajamas, and then brought them into the bedroom and sat them down on the nightstand next to his bed. All three were quiet for a moment, until Harold spoke up. “Could I tell you girls something?” There was a pause, and then Harold nodded once and continued.

“I’m an only child, did you know that? It was just me and my mother and father, and boy, did they put a lot of stock into everything I did. They were on me all the time. Wanted me to do everything at a certain time, in a certain order, and they wanted me to do it right. For the most part it wasn’t so bad. A lot of things came naturally to me, especially my schoolwork. What was interesting about my parents though, was that they never really talked about my having any friends. It was never something that was outright expected of me. Strange, right? But even stranger, I was… okay with it, and I think I still feel the same way now. A lot of times I feel…uneasy around people. I don’t always understand their faces. They change so quickly, you know, and it’s so hard to tell if they’re honest. I used to look at faces too long…I knew they meant something. Now I try not to look at all, if I can manage it.”

“Not that I’ve never had friends,” he stammered quickly, not wanting the rabbits to take pity on him. “There was Thomas at the bank, and Ed, my college roommate…their faces weren’t as puzzling. But I still have trouble.” Harold paused, breathing heavily, as if telling this story had taken almost all the life out of him. He turned to the rabbits. “Oh, no, girls. I’ve never had trouble with you. Your faces are as clear as water to me.” He didn’t want to worry them. He wanted them to know, in the best words he could find, how welcome they were in his life. He smiled. “Maybe tomorrow, a happier story.” And with that, Harold turned off the lights and fell asleep.

Months passed in the house with Harold and the rabbits. Every morning, Harold would get up and bring Celia and Dolores downstairs to eat breakfast while he got ready for work. He was always sure to let them know if he was going somewhere before or after the bank, and exactly what time he would be home. With the rabbits, Harold was always true to his word. He never wanted to break their trust in him.

However, after a few weeks, he began to worry that the rabbits were frustrated over being alone all day. He didn’t want them to resent him. He worried that one day he might come home and they wouldn’t want to speak to him. They would go on all night, whispering only to each other, and Harold would have to give out apology after apology. In his worst fantasies, he worried that he would open the door and they wouldn’t even be there anymore.

So he began to bring them things. First, it was little colored lollipops from the glass jar at the bank. Blue for Celia, purple for Dolores. Then he decided they might want something a little more stimulating. So he began to pick them up books on tape from the local library. He would burst in the door, exclaiming “Celia, the librarian recommended this for you - I told him about your taste for romance tales - and it actually sounds quite good. Perhaps I’ll listen to it after you’re done. And Dolores, I got you another Agatha Christie, like you asked. I’m so glad you’ve taken an interest in her, she’s one of my favorites.”

Harold loved to discuss literature and philosophy and world events with the rabbits at the end of the day. As he talked to them, he felt as if a giant tangled ball of yarn in the pit of his stomach was unraveling. Tension disappeared from his shoulders and his heart pumped stronger. He liked how the house seemed to feel alive with the conversations and thoughts the rabbits might have had throughout the day. He always wanted to know what was on their mind, and never hesitated to share what was on his.

At night, he talked with them about things he felt truly weighed down by, the things in life that crept out from the darkness and made him sweat and shiver.

“I don’t want you two to worry too much over this,” Harold began one night in the middle of the summer, “but some days I get this flash of lightning in my stomach and it’s this terrible fear that I’m gonna die right there on the spot. It’s hard to explain it. At that moment, I’m so scared of being taken away from this Earth that I get the urge to go outside and just bury myself in the ground and never come out. I’m old, you know…don’t flatter me, Celia, I know my age…and I know where I’m headed. I’m scared though. I never stop being scared. In life, sometimes people don’t have anyone, and that’s alright, because there’s lots more to look at and think about on this Earth than just people. But when I die…there’ll be nothing. There won’t even be rabbits. There won’t even be rabbits…and how could I stand it then?” He looked over at Celia and Dolores. Their little faces were stoic, and Harold was glad that he hadn’t upset them too much. He just wanted them to understand. “I don’t know, girls. I’ve got you now, and some days that seems to be the only thing I feel like holding on to.”

Time continued to pass in the split-level house with Harold and the rabbits. Summer ended and September rushed in with an incredible storm. Harold closed the windows and drew the curtains, because although he and the rabbits agreed that they enjoyed the sound of the rain beating on the roof, the sight of lightning frightened them.

On the sixth day of the month, there was a torrential downpour outside, but Harold knew he had to go and get the mail. He had neglected to pick it up for a few days in his haste to get inside and talk with the rabbits about a new book, and he knew there were some important documents from the bank he was now late in filling out. Positioning himself under an enormous black umbrella, he practically treaded water all the way up to the mailbox. But before he could get there, his ears flooded with a familiar loud, “Hi Harold!” Harold looked up and saw Olive walking down the street towards him, fighting against the wind for possession of her polka-dotted umbrella. He waved to her, and then turned his attention to the mailbox. He took out his letters and shoved them under his coat, preparing to go back inside. But then came a wailing, “Oh, G---------!” from Olive, and Harold turned back around. He saw her umbrella, now running away down the street, flipped inside out. The wind had won the battle, and Olive stamped her foot in defeat. She made eye contact with Harold, knowing he had seen what happened. She was getting wetter and wetter standing unprotected in the rain, but made no move to go inside her own house. She just stood there in the street, looking at him. Her thick black glasses were moderately bedazzled and covered in raindrops, but Harold just knew that the eyes behind them were staring at him imploringly, hopefully. He finally caved in. “Why don’t you come inside?” he said wearily.

“Oh, really? Thank you so much!”

Harold allowed Olive to share space under his black umbrella, but didn’t hold the door open for her. Olive rubbed her wet glasses off with her hand, then stuck them back on her damp face indelicately so she could look around inside. “You have a lovely home,” she said politely, her eyes roaming.

“Thank you.”

“Hello, lovely things! Nice to see you again!” Olive’s eyes had hit the mantle, and she was waving at the rabbits. Harold became irritated. He wanted to tell Olive to please stop looking at Celia and Dolores right this very second, but he did not. He wanted to tell her that they were ladies with proper names and not “lovely things”, but he did not. As Olive moved around the living room, complimenting his taste in furniture and asking questions about the piles of books on tape sitting on the coffee table, Harold found himself looking apologetically at the rabbits every few seconds.

He went and sat down on the couch, and Olive followed. Harold cringed, realizing she had dripped water all over the floor and was now creating a rather large damp spot on the couch. He ran upstairs and got her a towel, which she used to dry off her shivering arms and legs and then sit on. She was silent for nearly two whole minutes while she worked with the towel, but Harold knew it wouldn’t last long. He was right.

“Some weather, huh?” she began. “Yesterday, my kids found some frogs on the playground - a whole family of them - and they had drowned! Isn’t that funny? Well, the irony, I guess, was the funny part…who ever heard of frogs drowning? But all the screaming and the crying, that… wasn’t so funny…”

Something was missing in Olive’s speech at that moment, and Harold noticed. Usually, her sentences continued all the way through with gusto, but this one had holes in it, and tapered off like a light at the end of a tunnel suddenly growing dimmer.

This made Harold uncomfortable, but it was a different kind of discomfort than the kind he usually felt when he listened to Olive’s stories. Usually the discomfort he felt included impatience, irritation, and a little bit of nausea that came from descriptions of animals in various stages of dismemberment. The present discomfort came from knowing that Olive was chipping at the edges, and there was something raw underneath.

There was a minute or two of silence between the neighbors. Harold cleared his throat. Olive bunched the fabric of her dress in her hands and squeezed it tight.

“I think I’m gonna be retiring soon,” she blurted out, deflating a little.

“That’s a shame,” said Harold softly.

He almost stopped the conversation there. He felt fatigued just thinking about all the ways he might try to approach the topic. He entertained the idea of feigning sick and telling Olive she should leave before she caught whatever he had. But when Harold looked up at his neighbor’s face, he saw her eyes go cloudy. He saw her cheeks droop and even thought he saw her fuchsia lips grow two shades dimmer. He read her face, and he realized he knew what it meant. He let Olive continue talking, but began to feel heat on his shoulder of Celia and Dolores watching him from the mantle. They were whispering to each other.

“It’s so sad,” Olive sighed, “you know? I just love my kids so much. Even when they’re grown and they come back to visit, I still love ‘em just as much as the day they said goodbye to me to go to first grade.”

Harold’s primary instincts told him to stop her now, to let her go. But he fought them. He reached out, just a little, to try to draw her back in. “Tell me something about them.”

Olive looked up at Harold in surprise. “Oh,” she exclaimed, the sound coming out like a hiccup. “Okay.”

“Sometimes…sometimes you talk to them, and they can see that you’re sad, you know, and they try so hard to patch you up with whatever they can. They’ll give you a piece of candy, or they’ll put a bandaid on your shirt right where your heart is. And even though they’re really not solving the problem at all… it’s like they are. Just by caring. And it’s just amazing because they don’t even know they’re doing it.”

Harold nodded. He reached out his hand to pat hers, but froze halfway there and quickly jerked it back into his lap. Harold was astonished. He looked down at the hand in his lap as if looking at a stranger who had just come up to him and kissed him full on the mouth. Olive noticed the half-gesture, and gave a small sideways smile, as if to thank Harold for trying. The whispering of the rabbits became louder in his ears. They were pulling him like a riptide, and his stomach dipped briefly in anxiety, but he swam against them and asked Olive to tell him something else about her students.

They talked for a few hours. Olive sniffled a bit and let a few tears leak out. Harold didn’t try to reach for her hand again, but the idea grew warm and cozy in his head and his hand moved infinitesimally closer to hers a number of times. She asked him about the bank. He promised to bring her home an orange lollipop at the end of the week. He let her borrow one of the books on tape and she said excitedly that she would call him up as soon as she was done to tell him what she thought.

Eventually, King Charles III started howling to be let outside for a walk, and Olive got up to go home. Harold nearly offered to walk her back, but something in his heart clenched like a fist, and he gave her only a simple wave and a smile from the front stoop.

“Well,” he said as he closed the door, “that was…that was okay.” There was a brief moment of peace, but then he turned to face the rabbits with one eyebrow raised. “Did you say something, Dolores?” The rabbit didn’t answer. Harold frowned. “What? Why are you looking at me like that?”

A heated conversation between Harold and Dolores began to unfold.

“You think I what?” he said, his volume climbing. “With Olive? No, no, it wasn’t! How could you think that? No, I’m not saying you’re crazy, I just think you’re…hey, don’t say that about her!…WHAT? Don’t call me that! Don’t ever say I did that to you!” Harold was turning red now, and he was shouting. He never yelled at the rabbits, not once had he ever raised his voice to them, but Dolores was being so…so…

“Why would you say that? How DARE you!”

Harold knew his temper was escalating. He caught his breath, tried to control himself, changed tactics. “I’m still here, Dolores! I’m still here for you! Talk to me, please!” He paused, waiting for her reaction, and then suddenly went very pale. His eyes widened. “Oh please don’t go silent like that, don’t. Dolores!” But her silence did not abate, and something inside Harold audibly snapped. He stopped pleading. She wasn’t speaking to him, she wasn’t listening. She was sitting there, just sitting there, burning right through him, looking at him like that…

Harold picked Dolores up off the mantle and squeezed her hard in his hands. “I said, DON’T LOOK AT ME LIKE THAT!” And he hurled Dolores onto the floor, where she shattered into pieces.

One ear went shooting out to the left, one went flying out to the right. The little fur-textured torso cracked and burst, dusting the wooden floor with chalky white innards. The yellow bow bounced twice and got stuck under the refrigerator.

In Harold’s mind, the sound of Dolores hitting the floor did not end after the immediate collision. It rang in his head over and over and over again as he stared at the broken body on the floor. “Oh god,” he whispered, his hands starting to shake. “Oh, god.” He bent down to the floor, knees and hips cracking in protest, but stopped just short of touching a little black fragmented eye. He stood up and whirled around to face Celia, still on the mantle, his eyes brimming with hysterical tears.

“Oh god, Celia, I’m so sorry, I…I didn’t mean to. Celia, please! Please believe me!” Harold’s hands balled into fists. His voice trembled. “You know me, Celia, you know I would never have meant to do something like this. I’m not a horrible man. I’m not! I’M NOT! Don’t say that! Please…” His fists unclenched and his arms opened wide. “I’ll make it better, I promise. I’ll fix her…I’ll fix her right now! It’ll be okay, Celia, it’ll be okay, I’ll fix her.” Harold began to run wildly around the house, opening every drawer and cabinet. Every object he found seemed utterly inadequate to perform the task at hand, and his panic increased every time he discarded something. Duct tape? No, no not tape, she’ll tell me she looks like Frankenstein…not staples, no…I need glue, Harold thought, I need glue!

But he didn’t have any. He almost dropped to his knees, wanting to explode with frustrated roars. Then he remembered something Olive had told him about a crafting room she had upstairs in her house. She said she had burned her fingers just the other day on her hot glue gun, and had made the situation infinitely worse by trying to suck on the hot-glue covered finger in order to stop the stinging.

Harold burst through his front door and out into the yard. It had stopped raining, and a dull mist hung over the street. People were beginning to peek their heads out of doorways, craning their necks up to the sky to see if there was going to be a rainbow. Harold ran next door and rang Olive’s doorbell three, four, five times in a row. When that got no answer, he started banging and hollering. “Olive! Olive! Are you there? I need your help with something! Olive?”

Harold stopped banging when he realized that there were no sounds of barking coming from inside the house. There were no sounds of barking anywhere on the street. He turned around. There was no car in the driveway.

He stepped back from the porch and lifted his hands to his head, pulling at his hair. Olive wasn’t there. Olive wasn’t there, and the thought of going back to his own house and seeing the carnage inside made Harold feel as if he were going to vomit. He tried to steady himself and take a deep breath. Go back, he told himself. Go back to them. But he couldn’t. He took a few steps towards his house and his stomach erupted in spasms. He coughed and gagged violently, wishing he could just get it all over with and retch his ruined heart onto the ground.

After the spasms subsided, Harold straightened up and looked around the street through tear-filled eyes. He was alone outside now, his shoes sinking in the mud. All the little heads that had been poking out of doors up and down the street were gone. There hadn’t been any rainbow.

Harold felt his aloneness like a curse, like a stench that flowed from every pore of his body. It was unbearable. He hugged himself and shook as if he were shivering, sobbing gently.

He stood in Olive’s yard for almost an hour that way. And then his face became stone. His arms dropped by his side. He walked back into his own house, closed his eyes, and fumbled around in the entryway for his wallet and his keys. He did not shut the front door completely. Harold got into his car, sniffed up the last of his tears with a great snotty inhale, and then he was gone.

* * * * *

Olive’s car pulled up into the driveway at eight o’clock that same night. She wiggled out of her tiny hybrid merrily, with three plastic drugstore bags on either arm. They cut into her wrists, striping her with purple. She cooed at King Charles III as he hopped down from the driver’s seat, tail wagging, and with great difficulty managed to open her front door and push him inside the house with her foot. She kicked the house door and the car door closed and practically skipped over to Harold’s.

“Harold!” she called. “I just wanted to come by and thank you so much for cheering me up earlier. I don’t mean to intrude twice in one day, but I was out running some errands with Charlie and I just saw some great little things that I thought you’d…” She stopped, noticing Harold’s door unlocked and hanging open. She raised an eyebrow cautiously. “Harold?” No response. She nudged the door open a little more and tried again. “HAROLD!” Finally, the weight of all her bags sent her toppling forward into the house, falling onto her stomach. The contents of the bags scattered all over the floor. “Oh, Jesus Christ!” Olive spat, pulling herself up. She started grabbing things as fast as she could, worrying that Harold would come down the stairs any second now and look at her like he sometimes did, like she was a circus bear in a tutu that had fallen off the tightrope. She started to grab handfuls of plastic beads, part of a project that would be her last hurrah at the kindergarten, and grabbed something that dug into the palm of her hand and made her squeal in sudden pain. She opened her hand and stared at Dolores’ right ear in confusion.

Olive eventually realized that Harold wasn’t home, and went back to her house with a furrowed brow and dark eyes. She left almost twenty messages for him in the next week, all of which went unreturned. Every so often, she looked out onto Harold’s yard, King Charles III oddly silent at her side, unable to shake the image of one broken ceramic rabbit on the floor, and one ceramic rabbit on the mantle, staring coldly at nothing, already gathering dust.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.