All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Springtime in Munich

March 12, 1950

Munich, West Germany

March was a difficult month to love. The earliest part of the month was absolutely no different than January and February, save for the unpleasant freezing rain that it brought. It was one of those months that rested on the boundary between seasons and helped transition one to the next. Much of February’s snow had melted away, though a few grungy clumps and puddles rested at the street curbs. People still donned their heavy winter wear - jackets, gloves, scarves, boots - and only ventured away from their warm houses when it was absolutely necessary. While the snow and ice was thawing away, the first of many tiny green buds were beginning to appear on the trees’ branches. The leaves would not sprout and the flowers would not bloom for some time, but at the very least, it was a start.

Springtime was slowly but surely arriving in Germany. The Germans had survived the longest, harshest winter they had ever known. Innocent human lives had been systematically destroyed as if they were worth nothing. A catastrophic war left millions upon millions of soldiers dead. The horrific Nazi regime had permanently tarnished his country’s reputation. The country had been split down the middle, the west ruled by Americans and the east ruled by the Soviets. Despite the hardships of the past decade, the German people were determined to keep pushing forward. The ruined economy was on its way to recovering. Buildings, towns, families, and lives were in the process of being rebuilt. Life would return to normal with persistence and cooperation. Even the cruelest winter eventually gave way to spring.

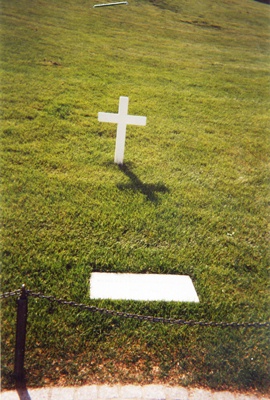

As Werner Keller contemplated this, he found it ironic that he was entering the one place where life never, ever moved forward. The military cemetery was a quiet, serene spot nestled away from the commotion of the busy city. The most recent gravestones - white, bare, completely identical except for the names - were lined neatly in rows close to the entrance. The ones who were unfortunate enough to die but were lucky enough to have been brought back to Germany rested there. The new flag, colored with bands of red, gold, and black, fluttered high above the cemetery.

Having a grave was such a convenient thing, a real luxury that most people never considered. The majority of people tended to push such a depressing thought out of their minds. Why should someone care about where they were buried? They were dead. They couldn’t protest. Werner knew that when he died, though, he wanted to have his own little patch of grass with a clear marker bearing his name. He wanted a place that was distinctly his, where his family members could go to visit him and remember him. Nobody else in his family had been granted such a privilege. His parents and sister had burned and blown away with the ashes of the ruined Dresden. His brother had been tossed haphazardly into a mass grave outside of a Soviet prison camp to rot with thirty other frozen bodies.

Werner wandered past the newest graves containing soldiers that had been just like him only years ago. As he walked deeper and deeper through the maze of graves, the headstones seemed to age. He moved past the victims of the Great War, his father’s generation. It was when he found himself in the very depths of the cemetery that he stopped. Here, the grass was a little wilder, the trees were shadier, and the stones had withered away with age. The markers surrounding him displayed dates mostly from the nineteenth century, though there were a few eighteenth century stones here and there. The one he stopped in front of was little more than a slab of bare rock - grooves and shapes on the surface hinted at letters and dates, but anything legible had weathered away. He wasn’t sure who rested beneath the grass, but he still “borrowed” the site for his own purposes.

“Happy twenty-sixth birthday, Friedrich.”

His hands folded neatly behind his back, Werner stared down at the gravestone as if he could see his younger brother’s face reflected in it. A handsome face with a dimpled chin, much more youthful and open than Werner’s own. Bright blue eyes, his mother’s eyes, always curious and carrying a hint of mischief. A head of thick, fluffy blond hair that never seemed to stay neat no matter how much he combed it. Werner preferred to envision the Friedrich he knew growing up, the one who always had a smile on his face and a funny story to tell. He tried his hardest to push the glassy-eyed, rail-thin frozen body he had seen out of his mind for good, but somehow it kept sneaking back.

He had been eighteen years old. A young boy handed a uniform and a gun and thrust into the cruel, unpredictable environment that was the Eastern front. He hadn’t asked to be a part of this war - the draft had snatched him away from his home, his promising future at university. Operation Barbarossa had been an enormous operation that required all of the manpower the German people could possibly spare, and it had been nothing but the costliest of mistakes. There was so much of life that he would never experience. Werner saw it as his duty to visit Friedrich every year on his birthday and inform him of what was happening. Doing so always comforted him; it almost made him feel as if Friedrich wasn’t a dead man, but someone who simply lived far away. It was an annual letter to someone who would never respond.

“Helena just had a baby girl in October,” Werner said, lifting his eyes to the sky and thinking of his wife and new daughter. “We named her Frieda, after you. She‘s so beautiful, and I know you would adore her. She definitely takes after Helena more than me, which is always a good thing.” The man allowed himself a half-hearted chuckle before continuing. “Although I do see a bit of Johanna in her, too. Our sister was always a feisty little thing growing up, and I’m afraid Frieda’s the same way. She’s already broken two of Helena’s favorite dishes and she loves to smear dirt from the potted plants all over the place. We can’t let her out of our sight for a second.”

A particularly harsh breeze blew through the cemetery, rustling the trees’ bare branches and causing Werner to bury his chin into his chest. The chill chased away the happy thoughts of his wife and daughter and brought back memories of the Russian prison camp. Werner had been a Wehrmacht lieutenant, the last surviving member of his squadron. They had discovered him hiding among rubble like a rat with a scoped rifle clutched in his gloved hands. Instead of killing him on the spot, the Soviets brought him to a labor camp, figuring that perhaps even the lowest-ranking of officers could be valuable to someone. It was here, in this impossibly cold wasteland, that Werner was reunited with his brother, a private.

“You never lost hope, Friedrich, not even for a second,” Werner continued, his voice taking on a heavier, more serious tone. “I witnessed young men die in those camps - not on the outside, but on the inside. You always stayed alive.” Werner had watched everything that was good in those young men wither away and disappear. They started as spirited, enthusiastic young soldiers, eager to serve their country and their cause. As the bone-chilling cold of the Russian winter arrived, morale dropped until it existed no more. The Germans who worked themselves to the death in the Soviet camps were not men, but half-frozen skeletons with dead eyes who moved stiffly and mechanically. As more and more men were lost to the winter, the prisoners became convinced that there was nobody out there that could save them.

Werner remembered those frigid days only too well. The sky stayed a dreary shade of gray. There was no snow or rain, not even a breeze - it was almost as if time had stopped in the camp. The prisoners had worked tirelessly for hours every day to reconstruct a railroad that German troops had destroyed. His brother had worked diligently at his side, clinging to the hope that the Soviets would spare them if they worked hard enough. Friedrich had always been ready with a story about home. He never used the word “if” - “if we go home” and “if we win the war” never left his mouth. It was “when we go home” and “when we win the war.” Werner had foreseen the end with the first violent cough to escape Friedrich’s throat. His movements became sluggish, he lost weight at an alarming rate, and he could barely last a minute without coughing. One morning just two weeks later, Friedrich did not wake up.

“When you…left me, I thought I would be next,” Werner sighed. His will to fight had died along with Friedrich. He was content to let the Russians do whatever they wanted with him. “Then our men discovered the camp. Rescued us and brought us back to safety. I wanted to carry on.” Something had awakened in him after the rescue. He wanted - needed - to fight. He would not stop until he made sure that his brother did not die in vain. Somehow Werner had lasted until the German surrender in 1945. Was it due to luck, willpower, or a combination of the two of them? He still didn’t know.

“I won’t let them demonize you. Let them make monsters of the SS, Hitler, the Nazi Party. They’re the ones to blame for destroying our country and our people. They’re going to burn in Hell for what they have done. But not you, brother. You didn’t ask to join the military. You didn’t burn down Jewish houses and slaughter innocents. You were only doing what every good soldier is supposed to do. You and everyone else like you - the British, Americans, Germans, Russians, everyone - were simply men fighting for their homelands. And that is nothing but honorable.” It was hard, so hard for Werner to think of the members of the Allied forces, especially the Soviets, as human. Deep down, he knew they were all the same.

The German man looked up at the graying sky as a drop of rain splattered onto the tip of his nose, followed by another and another. The light, misty drizzle had appeared all of a sudden, as if telling him that he had said enough. He had a wife and a daughter to return home to. The past couldn’t be forgotten, but he had to think of what lay ahead for him. Friedrich would always be stuck in his memories, and that was the way it would be until Werner, too, joined him.

“You were the soldier I always wanted to be, Friedrich. Happy birthday. I’ll visit you again soon. I love you and I miss you.”

With that, Werner Keller turned around and, for the time being, let the grave that would be Friedrich’s alone where he had found it. The springtime rain felt refreshing to him, not chilling and unpleasant. It felt new.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.