All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

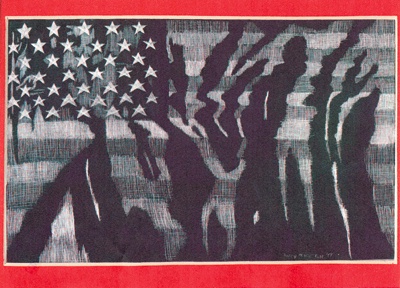

The Oath MAG

I walked into the stuffy government room. Rows of plastic chairs were lined up in front of the podium. The fluorescent office lights flickered. A modest American flag hung in the corner, its stripes folded across its stars. As I walked up to the registration table, a receptionist jotted down my name and, giving me a rolled-up paper flag, told me to have a seat.

Here in this room, one hand holding a red, white and blue sheet of paper taped to a barbecue skewer, the other placed lightly on my chest, I became a citizen of the United States.

A woman in a suit came over to take my green card and information sheet. I never got either back. She then proceeded to call each person in the room (there were about 40 of us) to sign papers.

After four hours of what could only be described as ceremonial sitting, a distinguished looking gentleman walked up to the podium, asked us to raise our right hands, and recite each part of the naturalization oath after him.

I was following along pretty well until he said,

“that I will bear arms on behalf of the United States when required by law; that I will perform work of national importance under civilian direction when required by law.”

I shouldn't have been surprised when I heard this; citizens are subject to the draft, of course, but no one had ever mentioned the draft. After all, becoming a citizen was a time of congratulations, of celebration, not of obligation. It was about life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, right? No one ever highlighted the “bear arms” part.

But the draft section was part of the oath. And how many other little obligations had I agreed to do by signing that paper? How many other parts had I not read closely enough? What had I signed up for in becoming a citizen of the country I had lived in? In Chinese, the United States is called “mei guo,” or “beautiful land.” Nowhere in such a description was there any mention of the draft: the only things I heard were the rustles of the amber waves of grain and ringing of freedom.

No matter how logical it seemed, how much sense it made in context, I couldn't help but balk for a second. I listened closely for his next line:

“and that I take this obligation freely without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; so help me God.”

Awkward.

We then recited the Pledge of Allegiance (most of which I had trouble remembering). Then people clapped. Families hugged. After the whole affair, though, I didn't feel different. I didn't suddenly feel patriotic. I didn't want to kiss the ground or wave my new flag. The truth is, I didn't feel any more American leaving that room than when I entered.

Don't get me wrong, I don't regret it one bit. Had you given me a choice between becoming a citizen or a Chinese immigrant living in America, I'd choose the States every time (God knows what China makes you promise in their naturalization speech.). But for the first time I had to consider that responsibilities came with the rights I had so keenly signed up for: responsibilities that every citizen of a nation should do, from jury duty to voting.

I realize now that I did not feel different simply because I was not different. I already had plenty of experience being American. I was American a month after I came here at the age of five. I was already American when I entered kindergarten. I was destined to be American the minute my parents decided that they would raise me here. I didn't assimilate by signing any papers or waving any flags: I did it by living here and breathing here.

Suddenly the obligations in the naturalization oath didn't seem so scary: I didn't suddenly sign up for a bunch of new responsibilities. I committed to them the minute I decided to live here. All I did was put it on paper.

I understood then what it meant to be a U.S. citizen. We weren't here to be proud and patriotic, bathing in the so-called glory of our newly found liberties. We received those liberties when we came to America, not now. We became citizens to assert our allegiance to the world we had already lived in for so many years.

And as a citizen, we should be excited to vote, excited to serve on a jury. I'm not excited to bear arms, but I certainly understand what it means to protect and preserve the liberties that I had taken for granted for all these years. To become a citizen is not to be patriotic or flaunt the American culture. It is to show respect for and trust in the government we live in. Whether someone was born here or stepped off a plane like me, that respect is the same.

Through that definition, I can now safely say that I take the obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion. So help me God.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.